The DIPOT project

List of publicationsExperimenting with 360⁰ and virtual reality representations as new access strategies to vulnerable physical collections: two case studies at the KB, National Library of the Netherlands

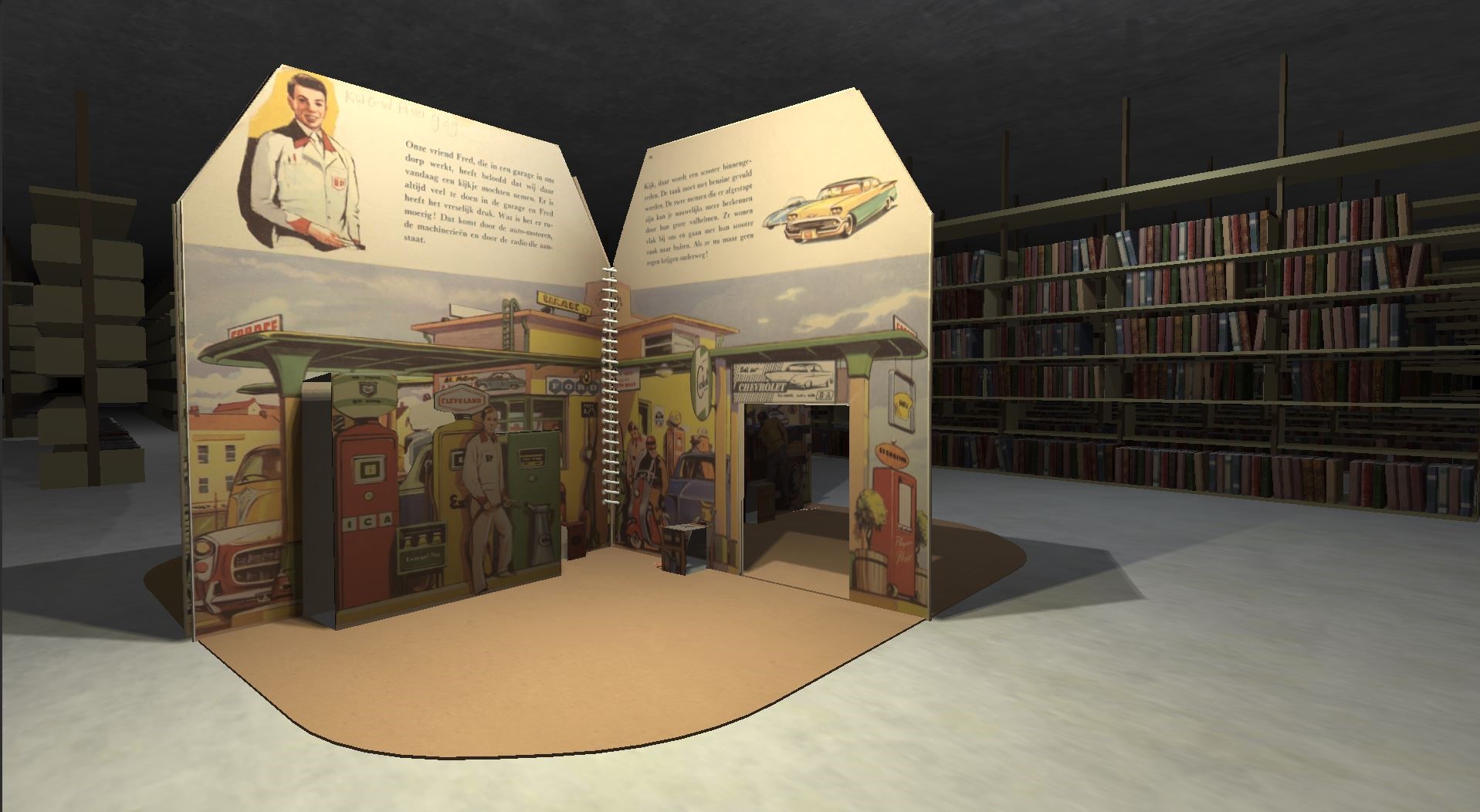

Abstract: In the late 1990s, the explosion of electronic resources has resulted in large scale digitisation projects and the need for preservation of digital information. The KB, National Library of the Netherlands, has been actively involved in these activities. As corollary consequence, it is proposing better ways to both preserve the physical library materials and improve their accessibility for educational purposes.

This paper describes two ongoing projects that involve preservation and public engagement. One describes the early stages of testing the applicability of 360⁰ imaging to support virtual access to the Special Collection storage. The second regards the VR production of children pop-up books for educational purposes. Both projects could inspire other library staff for introducing 3D/VR technologies and its possibilities to their audience. This paper describes both projects, show the methods used and discuss the expected outcomes.

Cite: Loddo, M., Boersma, F., Kleppe, M., & Vingerhoets, K. (2021). Experimenting with 360° and virtual reality representations as new access strategies to vulnerable physical collections: Two case studies at the KB, National Library of the Netherlands. IFLA Journal, 03400352211023080.

LinkedIn post

Museum Storage Facilities in the Netherlands: The Good, the Best and the Beautiful

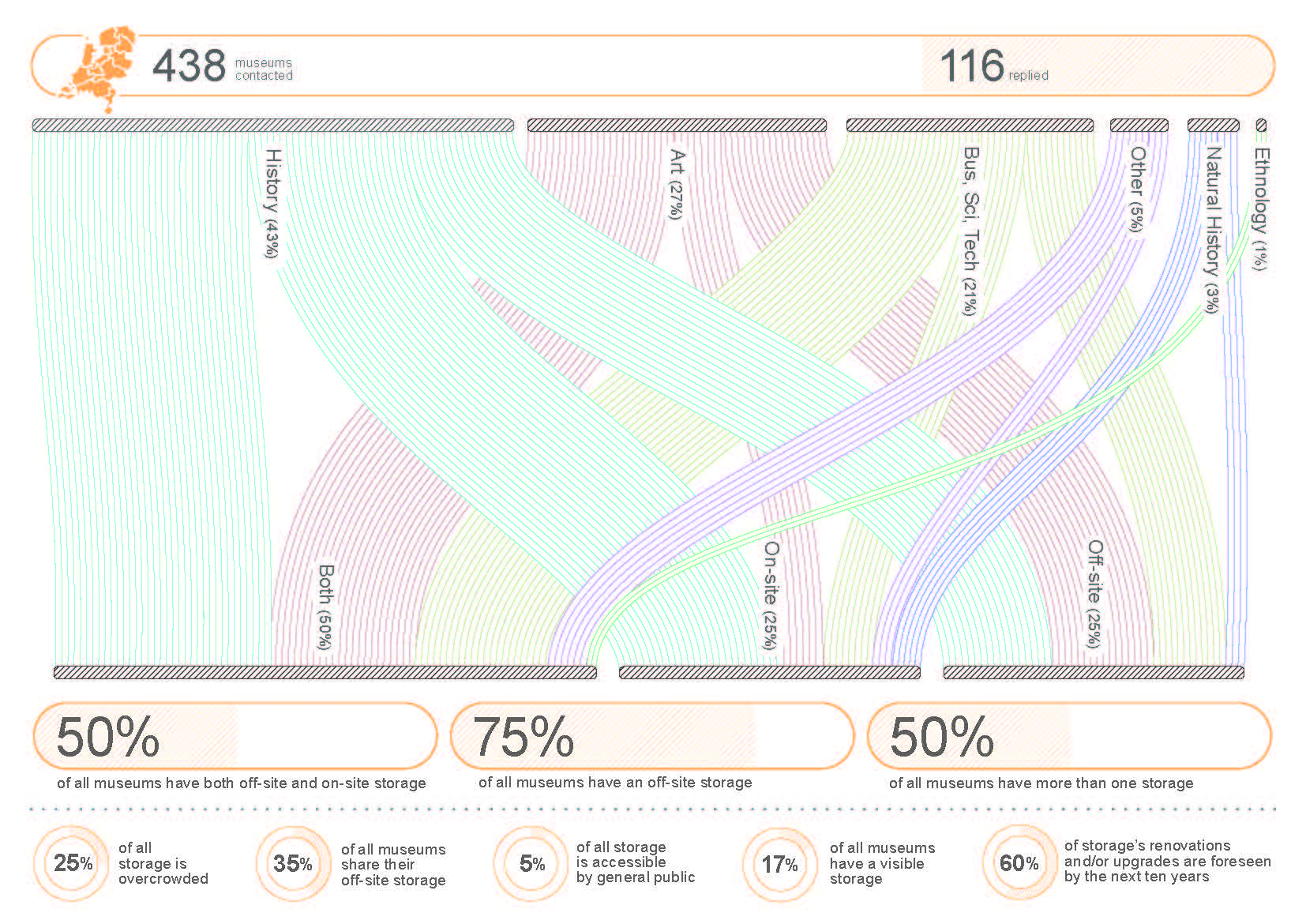

Introduction: Museum collections primarily exist in two states: they are either shown in displays or kept in storage. Most museums only display a small part of their collections, keeping most of them in storage. In 2019, the Netherlands counted 616 museums. While their cumulative number of objects grew from 69 million in 2015 to 78 million in 2019, the percentage of collections held in storage between 2015 and 2019—50 per cent to 80 per cent—remained more or less stable (De Erfgoedmonitor 2020). Objects held in storage are only accessible to a very small group of people. The fact that in most museums, the majority of the collection is kept in storage—for example, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam exhibits 8,000 of its approximately one million objects on permanent display shows that storage management plays a crucial role in the preservation of national heritage (Hoeben 2020). In 2011, when ICCROM conducted a survey among nearly 1,500 museums in 136 countries, the conclusions were startling: two out of three museums reported lack of space, one in two museums had overcrowded storage facilities, and one in four had insufficient object documentation (ICCROM-UNESCO 2011). Continue to read…

Cite: Ankersmit, B., Loddo, M., Stappers, M., & Zalm, C. (2021). Museum Storage Facilities in the Netherlands: The Good, the Best and the Beautiful. Museum International, 73(1-2), 132-143.

LinkedIn post

Built to last. Where are we with Heritage Depots in the Netherlands? (original title: Gebouwd om te bewaren. Waar staan we met Erfgoeddepots in Nederland?)

Info: In this publication, various professionals talk about their experience in developing, managing or researching heritage storage. With 21 contributions, the background is discussed from the design of storage to its day-to-day management. You may find two contributions of Marzia Loddo:

1) DIPOT a European project – a 360 degree view of collections in storage (original title: DIPOT een Europees project – een 360 gradenbeeld van collecties in depot)

2) An overview of the situation of the Dutch depots (original title: Een overzicht van de situatie van de Nederlandse depots).

Cite:

1) Loddo, M. (2021). DIPOT een Europees project – een 360 gradenbeeld van collecties in depot, in Ankersmit, B., & Stappers M., Gebouwd om te bewaren. Waar staan we met Erfgoeddepots in Nederland?, Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, pp. 55-61.

2) Loddo, M. (2021). Een overzicht van de situatie van de Nederlandse depots, in Ankersmit, B., & Stappers M., Gebouwd om te bewaren. Waar staan we met Erfgoeddepots in Nederland?, Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, pp. 62-63.

Immersive Technologies for Education in Heritage & Design. An online program adapted for the Architecture track in times of COVID-19

Abstract: Representation and communication of architectural and urban heritage narratives have been facing an unprecedented challenge in education, research and practice due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Blended digital and physical methods surfaced as a reasonable moving forward for architectural schools, especially in design studios. One of the biggest challenges has been keeping the engagement of students throughout a course whilst avoiding digital fatigue. Hence, concerning teaching, how can immersive technology and media facilitate heritage education and support the cultural and creative industries? Concerning researching, what is the role of storytelling in representing and communicating heritage narratives? The novel sub-field Digital Heritage (Wang et al., 2020) through gaming and virtual navigation/reality technologies and social media (Brusaporci, 2015; Gomes, Bellon, & Silva, 2014; Mortara et al., 2014; Shehade & Stylianou-Lambert, 2020) was the investigation focus theme for the Bachelor Minor course in Heritage & Design at Delft University of Technology. Such immersive technologies were chosen and designed to raise involvement and keep the engagement of students around values (why is heritage) and attributes (what is heritage?). At the same time, the program improved because it needed to be updated both to be COVID-19-proof and to problematize the new layers of digitalization in the city, known as cyber city and cyberculture (Bell, 2006). The episteme were three-fold Phenomenology (perception, sensory, embodied experience), Semiology (symbols, imagery, representation) and Material culture (user experience). The teaching methods were knowledge transfer, learn-by-doing and self-learning. The research methods were Simulation and Modeling [e.g., building (digital) models, prototyping] and Qualitative (e.g., interaction, interviews, visual/narrative devices) related to cyber-ethnography. The activities were structured in four phases: 1) Geogames – Pokémon GO, Harry Potter Wizards Unite, Ingress Prime; 2) Online serious games (Fig. 1); 3) Minecraft workshop (Fig. 2); 4) Virtual Navigation and Virtual Reality workshop (Fig 3 and 4). The results show that overall students responded well in terms of getting more engaged and motivated throughout the course as well as being able to create their own digital heritage narratives in a critically reflective way. They were able to learn from different resources and compare them providing valuable quanti-qualitative results. This digital heritage storytelling offers potentially a promising approach for educators, researchers and practitioners of architectural schools. Through valuable examples described in this work, the authors collaborated to provide an overview of immersive technology and media and its potential to be applied as a medium of digital architecture and urban heritage narratives.

Cite: D’Andrade, B. & Loddo, M. (2021). Immersive Technologies for Education in Heritage & Design. An online program adapted for the Architecture track in times of COVID-19, in CHNT Conference in Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, November, 2-4, 2021, Vienna